The structure

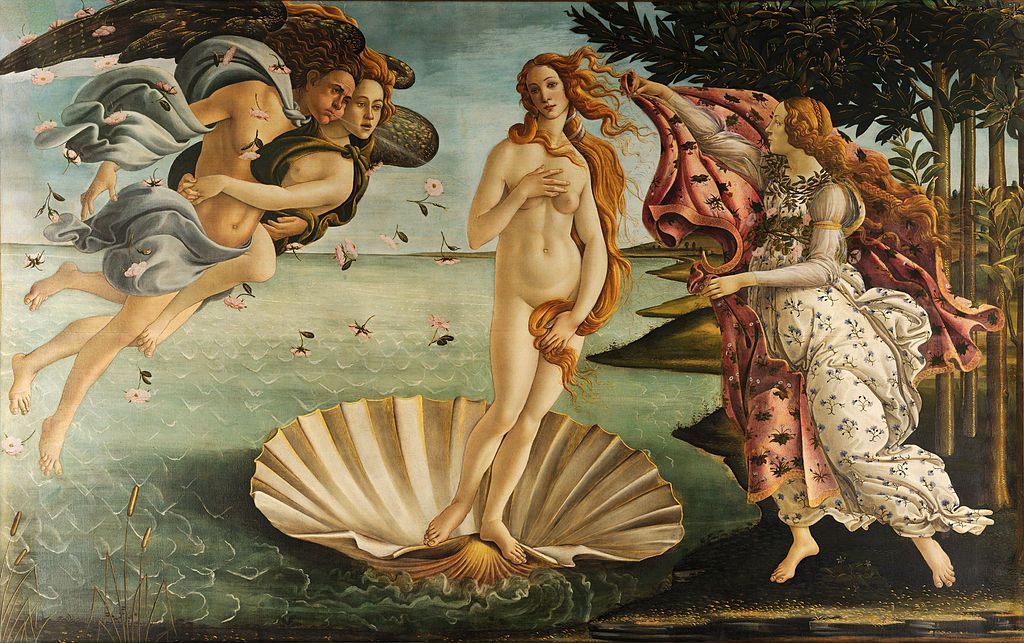

Sandro Botticelli's Birth of Venus, painted between 1484 and 1486, is considered by many to be the masterpiece of Italian Renaissance painting.

The balance of its composition, the way the groups of figures are arranged, the position of the horizon line, are by no means due to chance.

What was Botticelli's secret? How did he structure his work so that it appears so familiarly balanced?

To answer these questions, we need to delve into history, and understand the measuring tools used at the time.

Sandro Botticelli's work measures 1.72 m high by 2.78 m wide.

Why these precise measurements, and not 1.70 by 2.80 m, or 1.80 by 3 m?

To explain this choice of measurements, we need to look back into history, and in particular into the system of measurements used at the time.

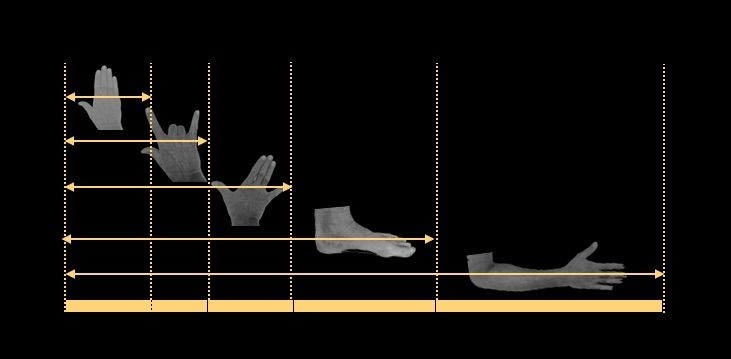

Before the advent of the metric system (1792), measurements were based on the proportions of the human body: inches, feet and cubits.

Cathedral builders had developed a system of five measurements that represented a true standard system to which all trades could refer on a building site: the palm, the palm, the empan, the foot and the cubit.

The palm was approximately 7.7 cm, the palm 12.4 cm, the yoke 20.2 cm, the foot 32.6 cm and the cubit 52.9 cm

If you take your own measurements and relate them to each other, you'll get an approximate, but not exact, result.

The point of the system developed by the Compagnons Bâtisseurs was to impose a common set of measurements on all site workers.

Today, we know that there is a constant ratio between these five measures. If you divide one of these measures by the previous one (e.g. cubit / foot, or palm / palm), you get an irrational number close to 1.618. If you multiply one of these measures by this number, you get the next measure.

If you multiply one of these measures by this number, you get the next measure (e.g.: empan x 1.618 = foot)

If we add the length of two adjacent measures, we obtain the third: palm palm = empan, or empan foot = cubit.

In the 19th century, this number was called the "Golden Number", but Luca Pacioli, whose mathematical treatise was illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci, called it the "divine proportion". Even in his time, Euclid spoke of "dividing a segment into extremes and averages" to obtain a harmonious ratio between two lengths.

A chapter on the Golden Ratio can be found at the end of this site.

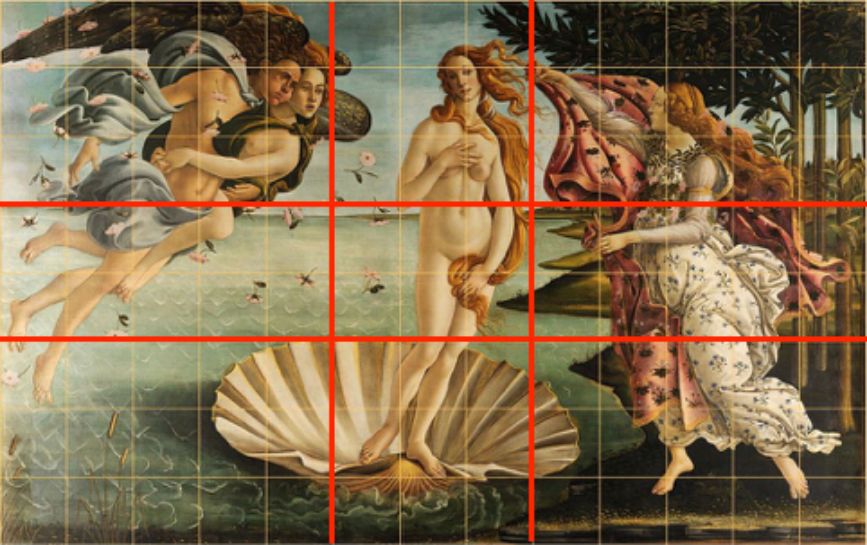

Let's return to the dimensions of the Birth of Venus. Converted to the measurements of the time, the painting measures 5 x 8 feet, or 8 x 13 empans!

This specific format, in which the ratio between width and height is equal to 1.618, is called the "Golden Rectangle".

It was customary at the time to divide the height of a picture by 8, and to place the horizon line on the 3rd or 5th horizontal position. In this sequence of numbers (3, 5, 8, 13), known as the "Fibonacci sequence", the ratio between one number and the one preceding it tends towards 1.618, the famous Golden Number. This ratio is identical to that governing the sequence of measurements used by cathedral builders in the Middle Ages: palm, palm, empan, foot and cubit.

Any pictorial or architectural work of the time was significant, i.e. charged with divine symbols. Religion was omnipresent. Sandro Botticelli's master was Fra Filippo Lippi, a monk painter of the early Renaissance. For Botticelli, using human proportions to structure his work was the result of secret know-how, but also a reminder of sacred notions.

Divine proportion", cited by Luca Pacioli and Leonardo da Vinci at the same time, alluded to geometry, human proportions and thus divine creation.

We wanted to find the largest common divisor between the width and height of the work (image above). The result is, in today's metric system, close to 21.3 cm, i.e. close to the measurement of an empan of the time. The empan measures the distance between thumb and little finger, hand apart.

A grid of regular squares based on this measurement (which may well have been the size of Boticelli's own empan!) has been superimposed on the famous painting. The red lines represent the division of the painting's height and width by the famous Golden Number.

First observation: the outer dimensions of the painting represent a "golden rectangle" (width / height = 1.618 = golden ratio)

Second observation: the division formed by the red lines reveals the structure of the painting: the precise location of the horizon line, the positioning of the various characters and the shell that gives birth to Venus.

Third observation: the lines of the grid and those obtained by dividing the external dimensions by the golden ratio coincide perfectly!

Clearly, to give structure to his work, Sandro Botticelli used what the architect Le Corbusier called a "regulating layout" based on the measurements of his time, i.e. human proportions.

This system of proportions lends an overall balance and natural harmony to the various volumes making up the painting.

The figure below shows the internal proportions of the painting compared in proportion to the main units of measurement used in Botticelli's time: the empan, the foot and the cubit.

The image below shows the internal proportions of the painting compared proportionally to the main units of measurement used at the time of Boticelli; the span, the foot and the cubit.

Take a look at the video below: it explains how the structure of Botticelli's work was created from a complex regular layout. We'll look at the tool used in this video later.

Read more...