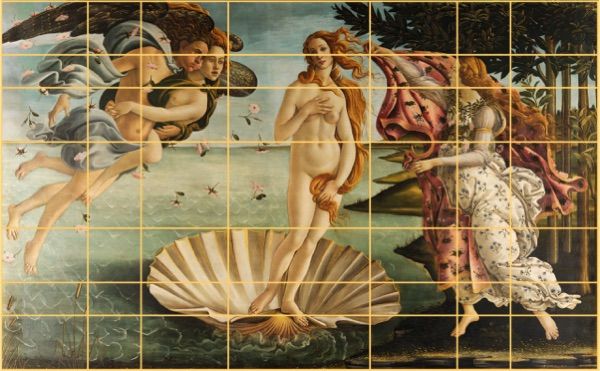

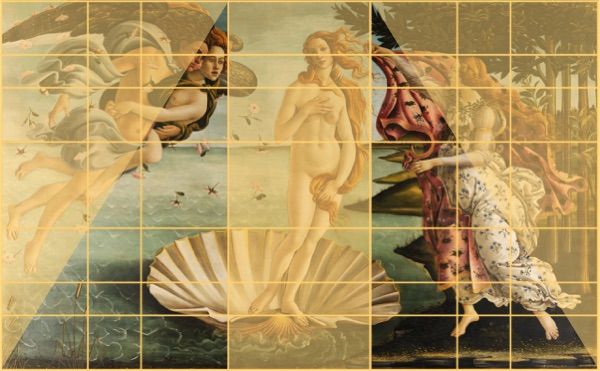

Three vertical subsets are shown below. The dimensions of the right and left rectangles are proportional to the outer dimensions of the painting. Each of these rectangles forms a Golden Rectangle. The various figures are arranged on the diagonal of these rectangles.

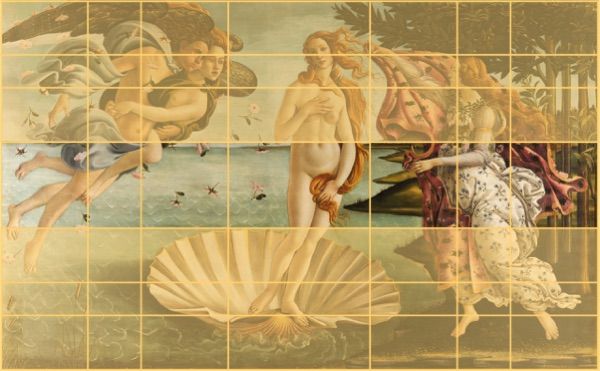

Another horizontal cutout below: the upper rectangle delimits the horizon line, on which Venus' navel is aligned. The lower rectangle contains the shell. These two rectangles are in 5/8ths proportion to the height of the painting, the proportion governed by the Golden Ratio.

Venus is in a central position. The rectangle containing her is equally proportionate to the outer rectangles. She's not in the middle of the picture: the axis of her body is on the vertical red line, again based on the same principle of proportionality, at 5/8ths of the median rectangle.